Reinterpreting Mansa Devi as a Climate Symbol in Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island

This blog is a part of an assignment of Contemporary literature in English . In this blog I'm going to discuss the Reinterpreting Mansa Devi as a Climate Symbol in Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island. Let's begin with my personal academic Information.

Personal Details:-

Name: Akshay Nimbark

Batch: M.A. Sem.4 (2023-2025)

Enrollment N/o.: 5108230029

Roll N/o.: 02

E-mail Address: akshay7043598292@gmail.com

Assignment Details:-

Topic:- Reinterpreting Mansa Devi as a Climate Symbol in Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island

Paper: 207

Subject code & Paper N/o.: 22414

Paper Name:- Contemporary literature in English

Submitted to: Smt. S.B. Gardi Department of English M.K.B.U.

Date of submission: 17 April2025

Points to Ponder:-

- Abstract

- Key Words

- Introduction

- About Amitav Ghosh

- Understanding Mansa Devi and Her Worship in Bengal

- Mansa Devi in Gun Island: Myth in Motion

- Ecofeminism and the Goddess as Nature’s Voice

- The Nature-Culture Divide and Mythological Resistance

- Environmental Warnings and Climate Catastrophes in Gun Island

- Conclusion

Abstract

This paper explores the transformation of the serpent goddess Mansa Devi from a mythological figure of religious reverence into a potent symbol of ecological resistance in Amitav Ghosh’s novel Gun Island. Traditionally revered in Bengal for protection and prosperity, Mansa Devi’s myth is intricately reimagined by Ghosh to embody warnings against climate change and environmental degradation. By tracing the intersections of folklore, migration, and environmental crises, this paper argues that myths such as Mansa Devi's can be revitalized to address pressing global concerns. Anchored in ecofeminist theory and cultural anthropology, this study underscores the evolving relevance of myth in contemporary literature and environmental discourse.

Keywords

Mansa Devi, Amitav Ghosh, Gun Island, Climate Fiction, Ecofeminism, Nature-Culture Divide, Migration, Serpent Worship, Myth, Environmental Crisis

Introduction

Mythology is a living, evolving form of cultural expression that adapts to societal changes while preserving ancient wisdom. In Gun Island, Amitav Ghosh reinvents the myth of Mansa Devi, the serpent goddess of Bengal, as an emblem of environmental consciousness. The novel challenges the dichotomy between modernity and tradition, and through the protagonist Deen, it gradually dissolves the boundary between myth and reality (Ghosh, 2019). Ghosh’s narrative aligns with the Anthropocene’s literary turn, where myth becomes a framework to understand ecological anxieties. By integrating mythology with climate migration and transnational crises, Ghosh illustrates how ancient stories can provide contemporary ecological insights (Jana, 2024).

About the Author: Amitav Ghosh

Amitav Ghosh, born in 1956 in Kolkata, is one of India’s most influential contemporary authors. Known for merging historical research with literary imagination, his works often explore colonial legacies, environmental degradation, and cultural displacement. Ghosh’s later writings, especially The Great Derangement (2016) and Gun Island (2019), reflect a growing concern with the climate crisis and critique the absence of environmental themes in mainstream fiction. Awarded the Jnanpith Award (2018) and the Erasmus Prize (2024), Ghosh’s interdisciplinary approach situates him at the intersection of literature, ecology, and global politics (Menon, 2021).

Understanding Mansa Devi and Her Worship in Bengal

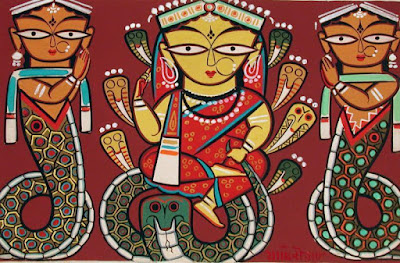

Mansa Devi holds a significant place in Bengali folk religion. She is a deity often depicted surrounded by serpents, representing fertility, healing, and vengeance. Her cult is especially prominent among rural communities and is deeply tied to the agrarian calendar. According to Bhattacharyya (1965), Mansa's roots lie in pre-Vedic tribal traditions, with possible Buddhist and tantric influences. The tale of Behula and Chand Saudagar encapsulates the conflict between rationalism and devotion, commerce and nature—a theme that resonates with Ghosh’s narrative.

The goddess’s iconography—clay pots, snake effigies, and oral ballads—reflects a distinctly feminine, earth-centric worship system. Saiki and Medhi (2021) note that Mansa Devi’s marginal position in the mainstream Hindu pantheon mirrors the marginalization of both women and nature in patriarchal structures. This folk dimension, often dismissed by elite Hinduism, becomes a powerful counter-narrative in Gun Island.

Mansa Devi in Gun Island: Myth in Motion

In Gun Island, Mansa Devi never physically appears, yet her mythological aura subtly guides the novel’s trajectory, revealing itself through symbols, coincidences, and inexplicable events. The novel begins with the protagonist, Dinanath “Deen” Datta, recalling a Bengali folktale from his childhood about Chand Saudagar, a merchant who defies the serpent goddess Mansa Devi and faces divine retribution. Ghosh introduces this story early in the novel as a seemingly quaint myth, which Deen initially treats with rational skepticism, calling it “just a story… a strange, tangled tale that made no sense” (Ghosh, 2019, p. 24). However, as the novel progresses, Deen's encounters with uncanny events—such as the sudden proliferation of venomous snakes in Venice and increasingly bizarre coincidences—lead him to reconsider the myth not as superstition, but as a narrative encoding deeper truths. As Cinta, the Venetian scholar and Deen’s friend, suggests, “Myths are not lies. They are stories that are truer than truth” (Ghosh, 2019, p. 172). Her character represents an alternative epistemology—one that embraces myth as a legitimate way of understanding the world, especially when scientific explanations fall short.

Ghosh does not merely retell Mansa’s myth but reactivates it in a global, contemporary context. For instance, Tipu—a young Bangladeshi migrant whom Deen meets—embodies the modern-day version of Chand Saudagar. Tipu’s forced migration due to socio-economic and environmental upheavals mirrors the merchant’s mythic journey across dangerous waters. In this way, Ghosh reframes the myth as a cyclical structure, continually reenacted in different historical and geographical contexts. As Aditi Jana (2024) observes, “Ghosh uses the legend of Mansa Devi not only to structure his narrative but to locate contemporary ecological displacement within a spiritual and cultural matrix.” Through Tipu, Rafi, and even Deen’s own transformation, the myth transcends its regional roots to become a global allegory for climate-induced migration, displacement, and survival. This approach allows Mansa Devi to evolve from a localized goddess into a diasporic symbol—her wrath and pursuit no longer confined to Bengal but spread across continents, reflecting the shared trauma of ecological collapse and human vulnerability.

Ecofeminism and the Goddess as Nature’s Voice

Amitav Ghosh’s reimagining of Mansa Devi in Gun Island also intersects powerfully with ecofeminist theory, particularly as it critiques the intertwined oppression of women and nature under patriarchal and capitalist systems. Ecofeminism, as defined by theorists like Sherry B. Ortner, posits that cultures have long identified women with nature—both seen as chaotic, passive, and in need of control—while men align with culture, rationality, and domination (Ortner, 1972, p. 9). In Gun Island, Ghosh subverts this framework by reviving Mansa Devi as a symbol of defiance and ecological agency. Her long-standing conflict with Chand Saudagar, a wealthy and influential male merchant, encapsulates the mythic struggle between nature (embodied by the feminine) and commerce (embodied by patriarchal power structures). Deen describes the myth as one where “the goddess had been denied her due… punished for demanding respect,” highlighting the socio-political subtext of Mansa’s narrative (Ghosh, 2019, p. 39).

Through the myth, Ghosh critiques how modernity continues to suppress voices of ecological wisdom, often rooted in indigenous, feminine, or non-Western traditions. Pushpa R. Menon (2021) points out that Ghosh’s portrayal of Mansa Devi is “a revival of the feminine principle in environmental ethics,” arguing that the goddess’s persistence in demanding recognition from a patriarchal society allegorizes nature’s own ignored warnings. Ghosh reinforces this symbolism through the various ecological disasters woven into the plot: snakes in Venice, dolphins beaching in the Sundarbans, and wildfires in California. Each serves as a metaphorical echo of Mansa’s mythic revenge, indicating that the Earth, like the goddess, is reacting to human neglect and abuse. Mansa’s divine anger, once mythologized as personal vengeance, now signifies planetary distress.

Moreover, Ghosh’s reimagining of Mansa Devi is not just about resistance but reclamation. Her transformation from a marginalized folk deity into a global ecological symbol reflects what Menon describes as a “reassertion of feminine agency in a world that has long dismissed both women and nature as inferior” (Menon, 2021, p. 3). This aligns with ecofeminism’s larger call to decenter human—and especially male—dominance in favor of relational, holistic, and inclusive worldviews. Mansa Devi becomes a literary embodiment of this shift: a mythic figure who once demanded faith, now demanding ecological accountability. Her voice, like the Earth’s, is persistent, resounding, and increasingly impossible to ignore.

The Nature-Culture Divide and Mythological Resistance

The Western epistemological tradition often separates ‘nature’ from ‘culture,’ privileging rationality over spirituality. Mansa Devi, emerging from the riverbanks and jungles of Bengal, is positioned outside this dichotomy. She is nature personified but demands cultural legitimacy. Her myth dramatizes the conflict between ecological forces and human arrogance.

Ghosh uses this dynamic to critique the capitalist logic of extraction and denial. Deen, a product of Western rationalism, initially dismisses Mansa’s story as mere folklore. However, his transformation reflects Ghosh’s broader thesis: that myths are repositories of ecological knowledge (Ghosh, 2019). As Bhattacharyya (1965) suggests, the serpent in Indian folklore often serves as a liminal figure—mediating between life and death, nature and civilization. Ghosh mobilizes this symbolism to question modernity’s blind spots.

Environmental Warnings and Climate Catastrophes in Gun Island

Ghosh intertwines myth and environmental catastrophe through a series of global events that echo Mansa Devi’s wrath:

Snakes in Venice:

The unexpected appearance of yellow-bellied snakes in a European city is a biological anomaly. It reflects the disruption of ecological boundaries due to climate change. Cinta interprets it as a sign—a reminder of the serpent goddess’s mythic power. As Menon (2021) argues, the snake here acts as an ecological messenger.Dolphin Beachings in the Sundarbans:

Mass dolphin deaths indicate toxic pollution and ecological imbalance. These events recall traditional fears of cosmic disorder, as seen in Mansa myths where water bodies are central to divine communication (Saiki & Medhi, 2021).Wildfires in California:

The uncontrollable wildfires are paralleled with the goddess’s rage. Just as Mansa punishes defiance with natural disasters, modern nature retaliates against ecological neglect.

Each of these crises becomes a narrative echo of the myth, suggesting that the planet is speaking in the language of catastrophe.

Conclusion:

Mansa Devi’s reinterpretation in Gun Island signifies the evolving role of mythology in literature. Ghosh’s genius lies in his ability to draw ancient folklore into global environmental discourse. The goddess’s transformation—from a rural deity to a planetary symbol—reflects a shift from passive reverence to active ecological engagement.

Ghosh does not diminish faith; he redirects it toward ethical responsibility. By reactivating Mansa Devi as a symbol of ecological justice, he reclaims myth as a narrative of survival, resistance, and warning. As Ortner (1972) and Menon (2021) suggest, such figures are crucial in envisioning a future where environmental consciousness is deeply rooted in cultural memory.

References

Bhattacharyya, Asutosh. “The Serpent as a Folk-Deity in Bengal.” Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 24, no. 1, 1965, pp. 1–10.

Ghosh, Amitav. Gun Island. Penguin Books India, 2019.

Jana, Aditi. “Interrogating Folklore and Transculturalism in Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island.” Vidyasagar University Digital Repository, 2024.

Menon, Pushpa R. “Ecofeminism in the Myth of Manasa Devi in Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island.” IJCRT, 2021.

Ortner, Sherry B. “Is Female to Male as Nature Is to Culture?” Feminist Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 1972, pp. 5–31.

Saiki, Meghali, and Debasmita Medhi. “Goddess Manasa: Origin and Development.” IAEME Journal, Feb. 2021.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment